TL;DW

Artificial intelligence is fundamentally shifting how we interact with technology, moving programming from arcane syntax to plain English. This has given rise to “vibe coding,” where anyone with clear logic and taste can build software. While AI will eliminate the demand for average products and hollow out middle-tier software firms, it simultaneously empowers entrepreneurs and creators to build hyper-niche solutions. AI is not a job-stealer for those with “extreme agency”—it is the ultimate ally and a tireless, personalized tutor. The best way to overcome the growing anxiety surrounding AI is simply to dive in, look under the hood, and start building.

Key Takeaways

- Vibe coding is the new product management: You no longer manage engineers; you manage an egoless, tireless AI using plain English to build end-to-end applications.

- Training models is the new programming: The frontier of computer science has shifted from formal logic coding to tuning massive datasets and models.

- Traditional software engineering is not dead: Engineers who understand computer architecture and “leaky abstractions” are now the most leveraged people on earth.

- There is no demand for average: The AI economy is a winner-takes-all market. The best app will dominate, while millions of hyper-niche apps will fill the long tail.

- Entrepreneurs have nothing to fear: Because entrepreneurs exercise self-directed, extreme agency to solve unknown problems, AI acts as a springboard, not a replacement.

- AI fails the true test of intelligence: Intelligence is getting what you want out of life. Because AI lacks biological desires, survival instincts, and agency, it is not “alive.”

- AI is the ultimate autodidact tool: It can meet you at your exact level of comprehension, eliminating the friction of learning complex concepts.

- Action cures anxiety: The antidote to AI fear is curiosity. Understanding how the technology works demystifies it and reveals its practical utility.

Detailed Summary

The Rise of Vibe Coding

The paradigm of programming has experienced a massive leap. With tools like Claude Code, English has become the hottest new programming language. This enables “vibe coding”—a process where non-technical product managers, creatives, and former coders can spin up complete, working applications simply by describing what they want. You can iterate, debug, and refine through conversation. Because AI is adapting to human communication faster than humans are adapting to AI, there is no need to learn esoteric prompt engineering tricks. Simply speaking clearly and logically is enough to direct the machine.

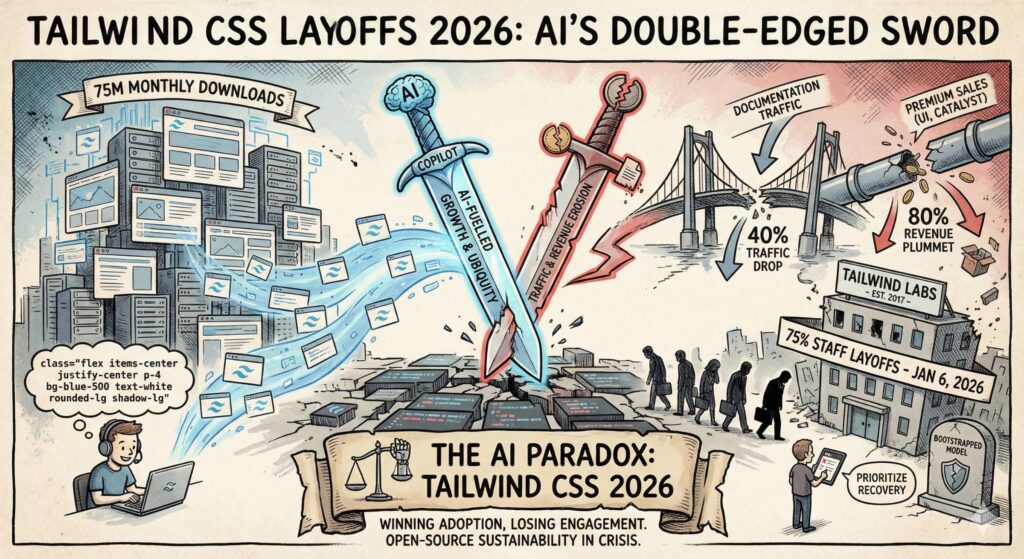

The Death of Average and the Extreme App Store

As the barrier to creating software drops to zero, a tsunami of new applications will flood the market. In this environment of infinite supply, there is absolutely zero demand for average. The market will bifurcate entirely. At the very top, massive aggregators and the absolute best-in-class apps will consolidate power and encompass more use cases. At the bottom, a massive long tail of hyper-specific, niche apps will flourish—apps designed for a single user’s highly specific workflow or hobby. The casualty of this shift will be the medium-sized, 10-to-20-person software firms that currently build average enterprise tools, as their work can now be vibe-coded away.

Why Traditional Software Engineers Still Have the Edge

Despite the democratization of coding, traditional software engineering remains critical. AI operates on abstractions, and all abstractions eventually leak. When an AI writes suboptimal architecture or creates a complex bug, the engineer who understands the underlying code, hardware, and logic gates can step in to fix it. Furthermore, traditional engineers are required for high-performance computing, novel hardware architectures, and solving problems that fall outside of an AI’s existing training data distribution. Today, a skilled software engineer armed with AI tools is effectively 10x to 100x more productive.

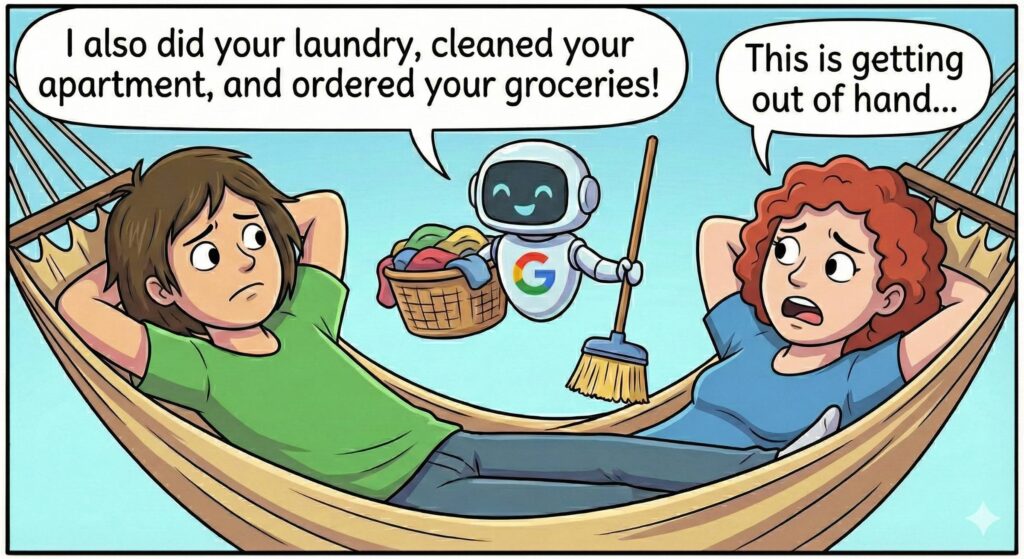

Entrepreneurs and Extreme Agency

A common fear is that AI will replace jobs, but no true entrepreneur is worried about AI taking their role. An entrepreneur’s function is the antithesis of a standard job; they operate in unknown domains with “extreme agency” to bring something entirely new into the world. AI lacks its own desires, creativity, and self-directed goals. It cannot be an entrepreneur. Instead, it serves as a tireless ally to those who possess agency, acting as a springboard that allows creators, scientists, and founders to jump to unprecedented heights.

Is AI Alive? The Philosophy of Intelligence

The conversation around Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) often strays into whether the machine is “alive.” AI is currently an incredible imitation engine and a masterful data compressor, but it is not alive. It is not embodied in the physical world, it lacks a survival instinct, and it has no biological drive to replicate. Furthermore, if the true test of intelligence is the ability to navigate the world to get what you want out of life, AI fails instantly. It wants nothing. Any goal an AI pursues is simply a proxy for the desires of the human turning the crank.

The Ultimate Tutor

One of the most profound immediate use cases for AI is in education. AI is a patient, egoless tutor that can explain complex concepts—from quantum physics to ordinal numbers—at the exact level of the user’s comprehension. By generating diagrams, analogies, and step-by-step breakdowns, AI removes the friction of traditional textbooks. As Naval notes, the means of learning have always been abundant, but AI finally makes those means perfectly tailored to the individual. The only scarce resource left is the desire to learn.

Action Cures Anxiety

With the rapid advancement of foundational models, “AI anxiety” has become common. People fear what they do not understand, worrying about a dystopian Skynet scenario or abrupt obsolescence. The solution to this non-specific fear is action. By actively engaging with AI—popping the hood, asking questions, and testing its limitations—users can quickly demystify the technology. Early adopters who lean into their curiosity will discover what the machine can and cannot do, granting them a massive competitive edge in the intelligence age.

Thoughts

This discussion highlights a critical pivot in how we value human capital. For decades, technical execution was the bottleneck to innovation. If you had an idea, you had to either learn complex syntax to build it yourself or raise capital to hire a team. AI is completely removing the execution bottleneck. When execution becomes commoditized, the premium shifts entirely to taste, judgment, extreme agency, and logical thinking. We are entering an era where anyone can be a “spellcaster.” The winners in this new economy won’t necessarily be the ones who can write the best functions, but rather the ones who can ask the best questions and hold the most uncompromising vision for what they want to see exist in the world.